Post by moira on Jul 14, 2008 22:08:09 GMT 2

Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973)

We had a long thread and discussion of Bachmann's poetry and her life

on my WomenWriters list at Yahoo, so I have chosen her today as our

foremother poet to remember. She is one of the central or important

writers and poets in German of the 20th century. So I send along 4:

First a translation (translator not named) of a powerful anti-war poem:

Every Day

War is no longer declared,

only continued. The monstrous

has become everyday. The hero

stays away from battle. The weak

have gone to the front.

The uniform of the day is patience,

its medal the pitiful star of hope above the heart.

The medal is awarded

when nothing more happens,

when the artillery falls silent,

when the enemy has grown invisible

and the shadow of eternal armament

covers the sky.

It is awarded

for desertion of the flag,

for bravery in the face of friends,

for the betrayal of unworthy secrets

and the disregard

of every command.

* *

Brotherhood (translated by Johannes Beilharz)

Each and every thing cuts wounds,

and neither of us has forgiven the other.

Hurting like you and hurtful,

I lived towards you.

Every touch augments

the pure, the spiritual touch;

we experience it as we age,

turned into coldest silence.

* *

from Michael Hamburger's Modern German Poetry

The Firstborn Land

To my firstborn land, to the south

I went and found, naked, impoverished

and up to my waist in the sea

city and citadel

Trodden by dust into sleep,

I lay in the light,

and with leaves of Ionian salt there hung

a tree's skeleton over me.

No dream fell down from there.

No rosemary blooms there,

no bird refreshes

his song in springs.

In my firstborn land, in the south

the viper leapt at me,

and horror of light.

O close,

close the eyes!

Press your mouth to the wound!

As I drank myself

and the earthquake rocked

my firstborn land to sleep,

all eyes I awoke.

Then life fell to my share.

Stone there is no dead thing.

The wick flares up,

if a glance ignites it. (1956)

* *

Fog Land

In winter my loved one retires

to live wit h the beasts of the forest.

That I must be back before morning

the vixen knows well, and she laughs.

Now the low clouds quiver! And down

on my upturned collar there falls

a landslide of brittle ice.

In winter my loved one retires,

a tree among trees, and invites

the crows in their desolation

into her beautiful boughs. She knows

that as soon as night falls the wind

lifts her stiff, hoar-frost-embroidered

evening gown, sends me home.

In winter my loved one retires,

a fish among fishes, and dumb.

Slave to the waters she ripples

with her fins' gentle motion within,

I stand on the bank and look down

till ice floes drive me away,

her dipping and turning hidden.

And stricken again by the blood-cry

of the bird that tautens his pinions

over my head, I fall down

on the open field: she is plucking

the hens, and she throws me a whitened

collar bone. This round my neck,

off I go through the bitter down.

My loved one, I know, is unfaithful,

and sometimes she stalks and she hovers

on high-heeled shoes to the city

and deeply in bars with her straw

will kiss the lips of the glasses,

and finds words for each and for all.

But this language is alien to me.

It is fog land I have seen,

It is fog heart I have eaten.

***************

While there is little poetry online, there are a number of biographies with some critical commentary.

This is a good one:

www.kirjasto.sci.fi/ibach.htm

According to one longer online literary source (a lengthy analysis), her radio plays are particularly remarkable.

Karen Achberger, St. Olaf College, Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 85: Austrian Fiction Writers After 1914.

A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by James Hardin, University of South Carolina and Donald G. Daviau, University of California, Riverside.

The Gale Group, 1989. pp. 24-39), writes:

""Der gute Gott von Manhattan," which was first broadcast in 1958, two levels of action alternate: the love story of the American student, Jennifer, and the European, Jan, and the trial of the "Good God of Manhattan" for Jennifer's murder; the love story is revealed in flashbacks narrated by the Good God and the judge in the courtroom. The theme, the impossibility of love in contemporary society, is a central one in Bachmann's oeuvre. Here love is undermined not from within but from without. Like the above site I referenced, Achberger emphasizes the woman-centered perspective of Bachmann's work. She gave five important lectures on poetics which she gave (at the University of Frankfurt between November 1959 and February 1960); here she discusses modernism, the limits of translation, utopian poetry. In her second lecture she argued (for example): "each poem has a new and unique grasp on reality and that this uniqueness is inherent in the idiom in which it is written;" in the third she "questions the accountability and authenticity of the narrative voice" (she talks about the use of "I") She was strongly socially engaged.

Malina seems the novel to read if you are just beginning or want to chose just one.

She is also known for her life (as so many women) and her long difficult relationship with Max Frisch, which relationship influenced his work (he caricatured her in one novel - very painful for her) and her life with him is reflected in her work too. Because of her relationship with him, she was not as productive for a long time as she perhaps could have been. Her later time in Italy (before she returned to Germany and died in fire set by herself by accident) seems to have been a very good one for her.

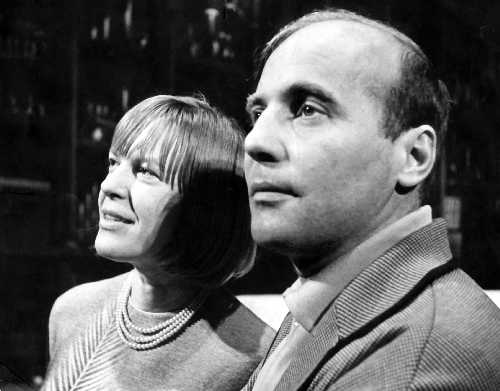

Reinhard Federmann, Milo Dor, Ingeborg Bachmann and Paul Celan 1952, Niendorf

On our list Fran Zichanowicz wrote as follows about two other not so well-known relationships:

"The love and friendship she felt for two other men in particular, if much less public and spectacular, had a far more constructive and productive influence on her work. The first, long almost unknown, was with Paul Celan, with whose work Bachmann entered into a poetic dialogue; the second with the musician mentioned in the biography Ellen posted, Hans Werner Henze.

They collaborated on several projects together, he setting some of her poems to music, she writing libretti for a couple of his operas, including his version of Kleist's Prinz von Homburg. He was also the one who most tried to shake her out of her post-Frisch depression and creative slump and urged her to concentrate on what should really matter to her: her work. He offered her a permanent home and work place with him in Italy, where she'd lived with him for a while before, but she never took him up on it."

Ingeborg Bachmann und Hans Werner Henze

Cheers to all,

Ellen